Recent article by a respected economist. Well worth a read.

Saul Eslake: 50 Years of Housing Failure

Address to the

122nd Annual Henry George Commemorative Dinner

The Royal Society of Victoria, Melbourne

2nd, September 2013

by Saul Eslake

Introduction

I appreciate very much the opportunity to talk to you at the 122nd Annual Henry George Commemorative Dinner.

Henry George was one of the more innovative economic thinkers of the

19th century, and it is in some ways a pity that his work is not better

known among those who do know at least a little of the history of

economic thought, as that of some of his contemporaries such as John

Stuart Mill, William Stanley Jevons, or Alfred Marshall still is today.

I first ran across him when I was studying Australian History at Year

12, and focusing in particular on the Great Depression of the 1890s. I

learned then that George’s advocacy of a single tax on the unimproved

value of all privately-held land had found favour with sections of the

then newly-emerging Australian labour movement.

Perhaps for that reason, those Australians who have actually heard of

Henry George usually place him on the left of the political spectrum.

Yet that is a gross over-simplification. He was also a strident advocate

of restrictions on Asian immigration – as was the Australian Labor

Party in its early days, and indeed right up until the 1960s – although

these days, that is a position usually associated with the extreme

right. Like most other economists, he was concerned about the existence

and exploitation of monopoly power. And, also like most other

economists, in his time and today, he was an advocate of free trade,

pointing out that tariffs are not something that foreigners pay to get

their goods into the country which imposes them, but rather something

that a country’s government makes its own citizens pay in order to keep

foreigners’ goods out: or, as he put it, “it is not from foreigners that

protections preserves and defends us: it is from ourselves” (George

1905: 45-46).

Nor is the advocacy of a greater role for the taxation of land in

taxation systems an exclusively left-of-centre position. Adam Smith,

commonly if not entirely accurately regarded as the father of “laissez

faire”, proposed what he called ‘ground rents’ as ‘a proper subject of

taxation’ a century before Henry George (Smith 1776: Book V, Chapter 2).

Milton Friedman – who in no sense could be characterized as being

anywhere near left-of-centre (notwithstanding his principled advocacy of

the decriminalization of drug use) – once said that, in his opinion

“the least bad tax is the property tax on the unimproved value of land,

the Henry George argument of many, many years ago” (Friedman 1978). The

Economist – the antithesis of a ‘socialist rag’ – earlier this year

stated that “taxing land and property is one of the most efficient and

least distorting ways for governments to raise money”, citing an OECD

study suggesting that “taxes on immovable property are the most

growth-friendly of all taxes” (Economist 2013: 70).

The Henry Review of the Australian taxation system concluded that

“land is an efficient tax base because it is immobile; unlike labour and

capital, it cannot move to escape tax” and that “economic growth would

be higher if governments raised more revenue from land and less revenue

from other tax bases” (Henry 2009: 247). Henry George would have been

pleased.

All of this notwithstanding, very few economists – and I am not one

of them – would today accept that it would be either possible, or even

if it were possible, desirable, for a land tax to be the sole source of

government revenue, as Henry George advocated. He was writing at a time

when government revenue requirements were substantially smaller than

they are today; and when it was far less likely than it is today that

people could be ‘asset rich but income poor’. But there is still a very

sound case for the taxation of land to play a greater role in raising

revenue for public purposes than it does today.

Housing policy: a half-century of policy failure

Housing is important. It meets a variety of deeply personal needs,

including those for shelter and (ideally) security. It provides a sense

of attachment (the place where we live) and, for many people,

contributes to their sense of identity. These are pretty basic needs for

almost all of us, as human beings. In addition, for many people, it is

an important means of building wealth (and often the most important

one); and for some, it provides the foundation for starting a business.

In Australia, most of us are well-housed – at least in a physical

sense. Although it hasn’t always been the case, and it isn’t the case

for all Australians today (not least for Indigenous people), most of us

live in houses or apartments that are well-constructed, amply fitted

with various devices that make the accomplishment of household tasks

easier than it was in our great-grandparents’ day, and replete with

other appurtenances and chattels that in some way or other provide us

with enjoyment or add meaning to our lives.

That isn’t the case in many other parts of the world. In July, I

spent a week in Madagascar, which according to the IMF is the

sixth-poorest country in the world, measured in terms of

purchasing-power-parity per capita GDP. It ranks 151st (out of 186

countries) on the United Nations latest Human Development Index. People

in Madagascar are not, in general, well housed. From my own observation,

outside of the capital, Antananarivo, most people in Madagascar live in

wooden or mud-brick huts that, in many cases, are smaller than the

lounge room of a typical new Australian house, with roofs made of

thatch, and in many cases without glazed windows. It puts our housing

issues into a different perspective.

Reflecting the importance of housing to people’s well-being, as well

as to many broader objectives, Australian Governments of all political

persuasions have long purported to attach a great deal of significance

to goals such as promoting home ownership, improving housing

affordability, and increasing housing supply.

And, once upon a time, Australian Governments did actually pursue policies that promoted those objectives (see Charts 1 and 2):

- between 1947 and 1961, the housing stock increased by 50% -compared

with a 41% increase in Australia’s population over this period. The

Commonwealth and State Governments directly contributed 221,700, or 24%

of the total increase in the housing stock over this period, through

programs financed under the Commonwealth-State Housing Agreements, or

under the War and Defence Service Homes Schemes.

- during this period, the home ownership rate increased from 53.4% to

70.3% -the largest increase in home ownership in Australia’s history.

- between 1961 and 1976, the housing stock increased by a further 46%

-again outstripping the 33% increase in Australia’s population over this

period. During this period, the Commonwealth and State Governments

directly added a further 299,000 dwellings to the housing stock,

equivalent to 23% of the increase in the total housing stock over this

period.

during this period, the home ownership rate fluctuated between 68% and

71%, but remained at a high level by international standards.

In other words, during this period, Federal and State Government

housing policies were principally directed towards increasing the supply

of housing, and at increasing or maintaining home ownership rates. And

these policies actually achieved those objectives.

Chart 1: Growth in the population and housing stock, 1947-2011

Chart 2: Home Ownership rates accelerated post WW2

Chart 2: Home Ownership rates accelerated post WW2

Chart 3: Home ownership rates at Censuses, 1947-2011

Chart 3: Home ownership rates at Censuses, 1947-2011

There were downsides to these policies, of course – in particular,

many of the dwellings built by State housing authorities, and by the

private sector, were poorly located from the standpoint of access to

employment, lacked basic infrastructure and community services, and

inadvertently served to concentrate socio-economic disadvantage. But

they did ensure that a rapidly-growing population was at least

adequately housed, and they gave many families an opportunity to gain a

first foothold on the home ownership ladder that they would otherwise

not have had.

Even between 1976 and 1991, the housing stock increased at a much

faster rate – 41% than the population – 23% -although only 9% of

dwelling completions during this period were by the public sector.

But the relationship between growth in the housing stock and

population growth began to change after the early 1990s. Between 1991

and 2001, Australia’s population grew by 11.5% , while the housing stock

grew by only 18.3% -less than 9 pc points more than the population. And

between 2001 and 2011, while the population grew by 15.9%, the housing

stock grew by only 15.2%. That is, over the past decade, the housing

stock has grown at a slower rate than the population – for the first

time since the end of World War II.

This gradual narrowing in the ‘gap’ between the growth rate of the

housing stock and that of the population – to the point of eliminating

it entirely over the past decade – has come in the face of demographic

trends that would have warranted a widening of this gap:

- average family sizes declined between the early 1960s and the early

1990s, implying that more dwellings are required to accommodate the same

number of people;

- family breakdowns have meant that more dwellings are required to accommodate the same number of people; and

- population ageing has resulted in more people living alone, again

increasing the number of dwellings required to accommodate the same

number of people.

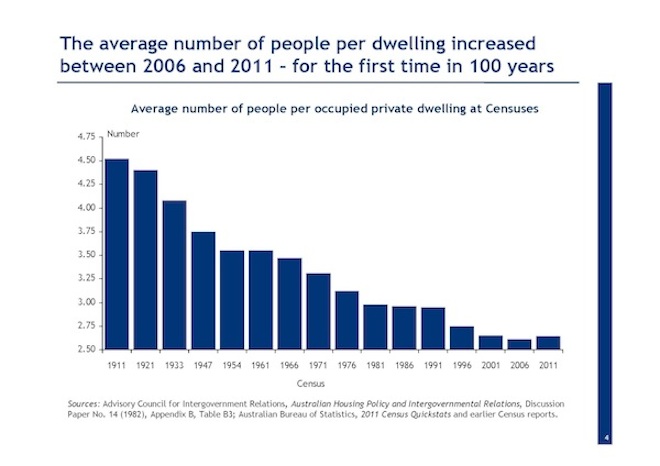

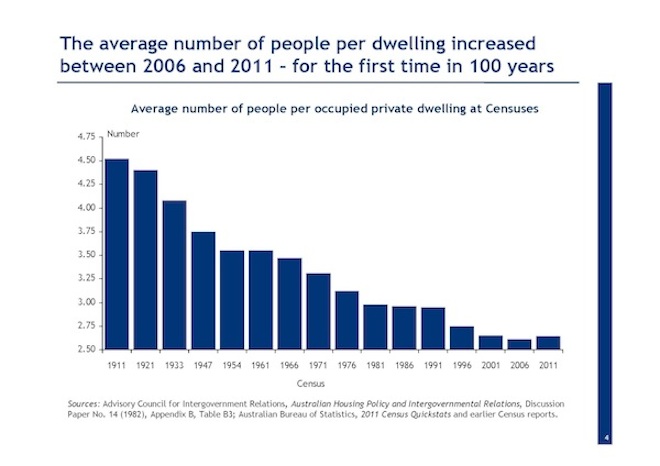

Yet, in the face of these ongoing trends, the average number of

people per dwelling actually rose (from 2.61 to 2.64) between the 2006

and 2011 Censuses – for the first time in at least 100 years (since the

first Commonwealth Census was conducted in 1911 – see Chart 3). From

1911 to 2006, the average number of people per dwelling had fallen from

4.52 to 2.61. It would seem that the widespread angst among ‘baby

boomer’ parents about how difficult it is to get their 20-(and in some

cases 30-) something children out of the family home has a sound basis

in fact.

Chart 4: Average number of people per dwelling at Censuses, 1911-2011

This is what the National Housing Supply Council, of which I’m a

member, means when it estimates that Australia has a ‘shortage’ of

housing relative to the ‘underlying’ demand for it – a shortage which it

last estimated to be of the order of 228,000 dwellings as at 30 June

2011 (NHSC 2012: 24-25).

That 228,000 figure is not an estimate of the number of homeless

people in Australia (which the ABS put at just over 105,000, a number

which included 41,390 people living in ‘severely overcrowded’ dwellings,

at the 2011 Census – ABS 2012). Rather, it reflects the gap between the

existing housing stock, and what the Council estimates the stock would

need to be if household formation patterns had remained essentially

unchanged over the past decade.

In passing, I should note that these estimates pre-date the results

of the 2011 Census, which has resulted in some downward revisions to the

estimated level of Australia’s population compared with those which had

been based on extrapolations from the 2006 Census, and which will lead

to some consequential revisions to these estimates of the housing

‘shortage’.

However, it would be a mistake to think – as some other commentators

have – that the revisions prompted by the 2011 Census results have

eliminated the ‘housing shortage’ which the National Housing Supply

Council and others had previously identified (see NHSC 2013: 107-123).

Nor, in my view, is the idea that there is a ‘housing shortage’ in

the sense intended by the NHSC contradicted by the work that Philip Soos

has undertaken for Earthsharing Australia, using data from Melbourne

water suppliers to show that up to 6% of residential properties across

the Melbourne metropolitan area may have been vacant during the second

half of 2011 (Soos 2012).

If those vacant properties aren’t available (for whatever reason) for

sale or rent then their existence does not detract from the existence

of a housing shortage – although it may well be, as Philip argues, that

an increase in land tax could prompt at least some of the owners of

those properties to make them available for sale or rent.

I think there are two principal reasons for the increasing failure of

the stock of housing to grow at a rate commensurate with the growth

rate (and changing needs) of the population:

First, the direct contribution of the public sector to growing the

housing stock has declined substantially. From the mid-1950s to the

mid-1970s, public sector agencies completed an average of 15,512 new

dwellings per annum (and they indirectly financed the completion of

another 3,600 dwellings annually through low-interest loan schemes).

From the mid-1970s to the early 1990s, they completed an average of

12,379 new dwellings per annum. But since then, they have completed an

average of less than 6,000 new dwellings per annum (indeed between 1999

and 2009 the public sector built fewer than 4,000 new dwellings per

annum, on average).

Second, state and local government planning schemes and policies for

charging for the provision of suburban infrastructure have made it

increasingly difficult for the private sector to supply new housing,

especially at the more affordable end of the spectrum.

This second reason has three distinct dimensions.

First, state and local authorities have imposed increasingly more

onerous requirements on developers for the provision of infrastructure

and services in new housing estates. While that undoubtedly represents

‘progress’ in many respects – and certainly adds to the amenity of

‘greenfields’ developments from the perspective of those who move into

them – it comes at a cost.

Second, local authorities have changed the way in which this

infrastructure and these services are provided, from a model based on

paying for them largely through debt, which was then serviced and repaid

out of subsequent increases in rate revenues, to one based on paying

for them through ‘up front charges’ on developers.

While this is consistent with a ‘user pays’ philosophy, and appeases

the growing voter aversion to public debt, it has meant (especially in

New South Wales, where developer charges have risen to much higher

levels than in other States) that developers find it increasingly

difficult to produce house-and-land packages at prices which are

affordable for first-time buyers and still make a profit, so they have

reacted by building a smaller number of more expensive houses targeted

at the trade-up market.

Third, metropolitan planning authorities and inner-city local

governments have made it increasingly more time-consuming and onerous to

undertake higher-density or ‘infill’ developments on ‘brownfields’

sites – in particular by imposing tighter planning controls, and by

providing more opportunities for objections to and appeals against

planning decisions.

As with the more onerous requirements for infrastructure provision in

‘greenfields’ sites, there are two sides to this story, and I have a

lot of sympathy with the desire of residents in established areas to

prevent developments which detract materially from their quality of life

(and/or from the value of their properties). But whatever perspective

one might take on that debate, there is no doubt that developments in

planning law have contributed to the mismatch between housing demand and

housing supply.

What is also noticeable about the last twenty years is that – despite

mortgage interest rates having been substantially lower, on average,

over this period (7.59% pa over the past 20 years, compared with 11.95%

over the preceding 20), and despite unprecedented expenditure on grants

to first home buyers – the overall home ownership rate has actually

declined by 5 percentage points, to 67% at the 2011 Census, its lowest

figure since the 1954 Census.

In fact the decline in home ownership has been even more pronounced

when one ‘looks through’ the effects of the ageing of the population,

which (among other things) means that an increasing proportion of the

population is within age groups where home ownership rates are always

(and for obvious reasons) higher than in younger age cohorts.

Research by Judy Yates of the University of NSW shows that home

ownership rates among younger age groups declined dramatically between

the 1991 and 2011 Censuses – from 56% to 47% among 25-34 year olds; from

75% to 64% among 35-44 year olds; from 81% to 73% among 45-54 year

olds; and 84% to 79% among those over 55. In fact the only age cohort

among whom home ownership rates didn’t decline over the past 20 years

was 15-24 year olds: but that was only because their home ownership rate

had already fallen 34% in 1961 to 24% by 1991 and didn’t decline any

further.

The decline in home ownership rates among younger age groups is

almost certainly due in part to changing preferences (including

partnering and having children at older ages, and greater importance

attached to proximity to employment or entertainment venues): but it

also undoubtedly owes more to declining affordability.

This is also evident in the fact that home owners are taking longer

to pay off their mortgages. According to the ABS’ just-released Survey

of Housing Occupancy and Costs (ABS 2013b), only 45.8% of home-owning

households owned their home outright in 2011-12, compared with 58.5% in

1994-95.

Chart 5: Home ownership rates by age cohort, 19961-2011

This may be partly due to the fact that households can, and do, use

mortgages for other purposes apart from simply acquiring the property

which is mortgaged: but I think it is far more due to the fact that

people need to borrow much more money initially in order to acquire a

property now than they did 20 years ago.

So, when set against the stated objectives of the housing policies

pursued by successive governments of various political persuasions, the

results have been dismal.

Although most Australians are, as I noted at the beginning,

physically well housed, it can no longer be said that we are, in

general, affordably housed; nor can it be said that the ‘housing system’

is meeting the needs and aspirations of as large a proportion of

Australians as it did a quarter of a century ago. And in making that

assertion I am thinking of the extent to which the housing system meets

the needs and aspirations of those who don’t want, or can’t and won’t

ever be able to, become home-owners, as well as of those who do seek

that status.

That is why I gave this talk the title, ‘Fifty Years of Failure’. In

order to develop that proposition more fully, I want to turn now to two

of the principal policies which governments of both persuasions have

pursued throughout this period.

Assistance to first home buyers

It’s hard to think of any government policy that has been pursued for

so long, in the face of such incontrovertible evidence that it doesn’t

work, than the policy of giving cash to first home buyers in the belief

that doing so will promote home ownership.

The Commonwealth Government started giving cash grants to first home

buyers in 1964 when, at the urging of the New South Wales Division of

the Young Liberal Movement (whose President at the time was a young John

Howard), the Menzies Government began paying Home Savings Grants of up

to $500 to ‘married or engaged couples under the age of 36’ on the basis

of $1 for every $3 saved in an ‘approved form’ (generally, with a

financial institution whose major business was lending for housing) in

the three years prior to buying their first home, provided that the home

was valued at no more than $14,000.

This scheme was abolished by the Whitlam Government in 1973 (in

favour of an income tax deduction for mortgage interest payments by

persons with a taxable income of less than $14,000 per annum);

re-introduced under the name of Home Deposit Assistance Grants (without

the age or marriage requirements and the value limits, and with a larger

maximum grant of $2,500) by the Fraser Government in 1976; replaced by

the Hawke Government in 1983 with the First Home Owners Assistance

Scheme, initially with a maximum grant of $7,000 (later reduced to

$6,000) and subject to an income test; abolished by the Hawke Government

in 1990; and then re-introduced as the First Home Owners Grant (FHOG)

by the Howard Government in 2000, without any income test or upper limit

on the purchase price of homes acquired, ostensibly as ‘compensation’

for the introduction of the GST (even though the GST only applied to the

purchase of new homes, and not to existing dwellings which the majority

of first-time buyers purchase). In this guise it was really just the

first of what became an explosion in ‘status-based welfare’ payments to

selected groups irrespective of needs during that decade. On two

occasions since 2000, the FHOG has been temporarily increased in

response to an actual or feared slump in housing activity (and in 2008,

in response to a feared decline in house prices).

Over the past decade, most State and Territory Governments have

‘topped up’ the basic FHOG payments to first-time buyers with grants

from their own resources, with some States providing even larger grants

to buyers meeting certain additional criteria (for example, the

Victorian Government provided an additional $5,000 for buyers of new

homes in rural and regional areas).

I estimate that the Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments

spent a total of $22.5bn (in 2010-11 dollar values) on cash grants to

first home buyers between 1964 and 2011.

Chart 6: Explosion in status based welfare

State and Territory Government also provide indirect financial

assistance to first-time buyers by partially or totally exempting them

from the stamp duty they would otherwise pay on their purchases. In

2011-12 alone, these were worth around $3bn.

Chart 7: Spending on cash assistance to first home buyers, 1964-65 to 2011-12

Governments have thus been providing cash handouts to first-time

home-buyers for almost half a century. Yet, as I mentioned earlier, the

overall home ownership rate has never been higher than it was at the

1961 Census, immediately before governments started going down this

path; and among the age groups which are supposedly most intended to

benefit from these handouts, home ownership rates have declined almost

vertiginously over the past two decades.

And it’s pretty obvious why. Cash grants and other forms of

assistance to first-time home buyers have served simply to exacerbate

the already substantial imbalance between the underlying demand for

housing and the supply of it.

In those circumstances, cash handouts for first home buyers have

simply added to upward pressure on housing prices, enriching vendors

(and making those who already housing feel richer) whilst doing

precisely nothing to assist young people (or anybody else) into home

ownership. For that reason, I often think that these grants should be

called ‘Existing Home Vendors’ Grants’ – because that’s where the money

ends up – rather than First Home Owners’ Grants.

Encouragingly, perhaps – after what in my case has been more than 30

years of putting this kind of argument – State and Territory Governments

appear at last to have gotten this message. Over the past 18 months or

so, every State and Territory Government has either abolished or at

least substantially reduced grants to first home buyers who buy existing

dwellings, whilst increasing their grants to those who buy new ones,

with a net effect of reducing the total spend on assistance to first

home buyers.

I have no doubt that some of the increased grants to first time

buyers of new homes will end up boosting developers’ or builders’

profits: but I accept that at least some of it will induce a supply side

response to any resulting increase in demand for new homes, while

considerably fewer taxpayers’ dollars will be wasted inflating the

prices of existing homes.

‘Negative gearing’

Another long-standing policy which I have long argued has not only

failed to deliver on its oft-stated rationale of boosting the supply of

housing – in this case for rent – but has actually exacerbated the

mis-match between the demand for and the supply of housing, as well as

having distorted the allocation of capital, and undermined the equity

and integrity of the income tax system, is so-called ‘negative gearing’.

It is perhaps a telling indication of just how generous Australia’s

tax system is to investors in this regard, compared with those of other

countries, that one usually needs to explain to foreigners what the term

‘negative gearing’ actually means (see for example RBA 2003: 4045).

‘Negative gearing’ originally allowed taxpayers in effect to defer

tax on their wage and salary income (until they sold the property or

shares which they had acquired with borrowed money, on which they were

paying more in interest than they received by way of dividends or rent).

However, after the Howard Government’s 1999 decision to tax capital

gains at half the rate applicable to other income (instead of taxing

inflation-adjusted capital gains at a taxpayer’s full marginal rate),

‘negative gearing’ became a vehicle for permanently reducing, as well as

deferring, personal tax liabilities. And the availability of

depreciation on buildings adds to the way in which ‘negative gearing’

converts ordinary income taxable at full rates into capital gains

taxable at half rates.

Chart 8: ‘Negative gearing’, 1993-94 to 2010-11

It’s therefore hardly surprising that ‘negative gearing’ has become

much more widespread over the past decade, and much more costly in terms

of the revenue thereby foregone (see Chart 6 above).

In 1998-99, when capital gains were last taxed at the same rate as

other types of income (less an allowance for inflation), Australia had

1.3 million tax-paying landlords who in total made a taxable profit of

almost $700mn. By 2010-11, the latest year for which statistics are

presently available, the number of tax-paying landlords had risen to

over 1.8mn (or 14% of the total number of individual taxpayers), but

they collectively lost more than $7.8bn, largely because the amount they

paid out in interest rose more than fourfold (from just over $5bn to

almost $23bn over this period), while the amount they collected in rent

‘only’ slightly less than trebled (from $11bn to $30bn), as did other

(non-interest) expenses.

If all of the 1.2mn landlords who in total reported net losses in

2010-11 were in the 38% income tax bracket, their ability to offset

those losses against their other taxable income would have cost over

$5bn in revenue foregone; to the extent that some of them are in the top

tax bracket then the revenue loss is obviously higher.

This is a pretty large subsidy from people who are working and saving

to people who are borrowing and speculating (since those landlords who

are making ‘running losses’ on their property investments expect to more

than make up those losses through capital gains when they eventually

sell them).

And it’s hard to think of any worthwhile public policy purpose which

is served by it. It certainly does nothing to increase the supply of

housing, since the vast majority of landlords buy established

properties: 92% of all borrowing by residential property investors over

the past decade has been for the purchase of established dwellings, as

against about 72% of all borrowing by owner-occupiers.

Precisely for that reason, the availability of ‘negative gearing’

contributes to upward pressure on the prices of established dwellings,

and thus diminishes housing affordability for would-be home buyers.

Supporters of ‘negative gearing’ argue that its abolition would lead

to a ‘landlord’s strike’, driving up rents and exacerbating the existing

shortage of affordable rental housing. They repeatedly point to what

they allege happened when the Hawke Government abolished negative

gearing (only for property investment) in 1986 – that it ‘led’ (so they

say) to a surge in rents, which prompted the reintroduction of ‘negative

gearing’ in 1988.

This assertion is actually not true. If the abolition of ‘negative

gearing’ had led to a ‘landlord’s strike’, as proponents of ‘negative

gearing’ repeatedly assert, then rents should have risen everywhere

(since ‘negative gearing’ had been available everywhere). In fact, rents

(as measured in the consumer price index) only rose rapidly (at

double-digit rates) in Sydney and Perth – and that was because in those

two cities, rental vacancy rates were unusually low (in Sydney’s case,

barely above 1%) before negative gearing was abolished. In other State

capitals (where vacancy rates were higher), growth in rentals was either

unchanged or, in Melbourne, actually slowed (see Chart 7).

Chart 9: Rents and vacancy rates in the mid-1980s

However, notwithstanding this history, suppose that a large number of

landlords were to respond to the abolition of ‘negative gearing’ by

selling their properties. That would push down the prices of investment

properties, making them more affordable to would-be home buyers,

allowing more of them to become home-owners, and thereby reducing the

demand for rental properties in almost exactly the same proportion as

the reduction in the supply of them. It’s actually quite difficult to

think of anything that would do more to improve affordability conditions

for would-be homebuyers than the abolition of ‘negative gearing’.

There’s no evidence to support the assertion made by proponents of

the continued existence of ‘negative gearing’ that it results in more

rental housing being available than would be the case were it to be

abolished (even though the Henry Review appears to have swallowed this

assertion).

Most other ‘advanced’ economies don’t have ‘negative gearing’: yet

most other countries have higher rental vacancy rates than Australia

does.

Chart 10: Rental vacancy rates in Australia and the United States

In the United States, which hasn’t allow ‘negative gearing’ since the

mid-1980s, the rental vacancy rate has in the last 50 years only once

been below 5% (and that was in the March quarter of 1979); in the ten

years prior to the onset of the most recent recession, it has averaged

9.1% (see Chart 8 above).

Yet here in Australia, which does allow ‘negative gearing’, the

rental vacancy rate has never (at least in the last 30 years) been above

5%, and in the period since ‘negative gearing’ became more attractive

(as a result of the halving of the capital gains tax rate) has fallen

from over 3% to less than 2%.

During that same period, rents rose at rate 0.8 percentage points per

annum faster than the CPI as a whole; whereas over the preceding

decade, rents rose at exactly the same rate as the CPI.

Similarly, countries which have never had ‘negative gearing’ – such

as Germany, France, the Netherlands, the Nordic countries and (low-tax)

Switzerland – have much larger private rental markets than Australia.

Some supporters of negative gearing also argue that since businesses

can deduct all of the operating expenses they incur (including interest)

against their profits in order to determine their taxable income, and

can also ‘carry forward’ net losses incurred in any given year against

profits earned in subsequent years so as to reduce the tax otherwise

payable, it is only ‘fair and reasonable’ that investors should be able

to do the same.

There are two flaws in this argument, in my view. First, a large part

of the appeal of ‘negative gearing’ comes from the way in which it

allows income which would otherwise have been taxed at the investor’s

marginal rate effectively to be converted into capital gains, which are

taxed at half the investor’s marginal rate. Businesses – if they are

incorporated, as most businesses these days are – can’t do that.

Companies aren’t eligible for the 50% discount on tax payable on gains

on assets held for more than one year.

Second, while individuals are allowed to deduct expenses incurred in

connection with producing investment income from their taxable income,

they aren’t allowed to deduct many types of expenses incurred in

producing wage and salary income.

To take an obvious example, wage and salary earners aren’t allowed to

deduct the cost of travelling to and from work; nor are they allowed to

deduct child care expenses.

Or, to take another example which may be an even closer analogy with

‘negative gearing’ for investment purposes, individuals aren’t allowed

to deduct interest on borrowings undertaken to finance their own

education as a tax deduction, even though that additional education may

contribute materially to enhancing their future earnings – and even

though any such additional future earnings will be taxed at that

individual’s full marginal rate, as opposed to half that rate in the

case of capital gains on an investment asset.

Let me be clear that I’m not advocating that ‘negative gearing’ be

abolished for property investments only, as happened between 1986 and

1988. That would be unfair to property investors.

Personally, I think ‘negative gearing’ should be abolished for all

investors, so that interest expenses would only be deductible in any

given year up to the amount of investment income earned in that year,

with any excess ‘carried forward’ against the ultimate capital gains tax

liability, rather than being used to reduce the tax payable on wage and

salary or other income (as is the case in the United States and most

other ‘advanced’ economies).

But I’d settle for the recommendation of the Henry Review (2009,

Volume 1: 72-75), which was that only 40% of interest (and other

expenses) associated with investments be allowed as a deduction, and

that capital gains (and other forms of investment income, including

interest on deposits) be taxed at 60% (rather than 50% as at present) of

the rates applicable to the same amounts of wage and salary income.

This recommendation would not amount to the abolition of ‘negative

gearing’; it would just make it less generous than it is at the moment.

It would be likely, as the Henry Review suggested, ‘to change investor

demand toward housing with higher rental yields and longer investment

horizons [and] may result in a more stable housing market, as the

current incentive for investors to chase large capital gains in housing

would be reduced’.

I could even accept the Henry Review’s recommendation that “these

reforms should only be adopted following reforms to the supply of

housing and reforms to housing assistance’ which it makes elsewhere,

even though I disagree with the Henry Review’s concern that these

reforms ‘may in the short term reduce residential property investment’.

I could also accept, grudgingly, that any of these changes could be

‘grandfathered’, in order to minimize opposition from those who already

have negatively geared investments, and who would understandably see the

modification or removal of ‘negative gearing’ without such a provision

as directly disadvantageous to them.

However, the alacrity with which both major political parties moved

to distance themselves from even these modest proposals in the Henry

Review when it finally saw the light of day a few days before the 2009

Budget doesn’t provide much grounds for hope in that regard.

What could be done instead?

I’ve argued that two of the principal long-standing government

interventions in the housing market – cash assistance to first-time home

buyers and ‘negative gearing’ – have not only failed to achieve their

stated objectives, but have actually exacerbated the difficulties facing

those whom these interventions are supposed to assist:

-

they have served to inflate the demand for housing – and in particular,

the demand for already-existing housing – whilst doing next to nothing

to increase the supply of housing.

-

they have therefore made housing affordability worse, not better.

-

and to the extent that the ownership of residential real estate is

concentrated among higher income groups – 36% of all property owned by

individuals, and 47% of all property other than owner-occupied

dwellings, is owned by households in the top 20% of the income

distribution (ABS 2013c) – they exacerbate inequities in the

distribution of income and wealth.

In passing, it is perhaps worth wondering why successive governments

of various political persuasions have been so unwilling to alter

policies which have not merely failed so abjectly to meet their stated

objectives, but have demonstrably had such an adverse impact on those

whom successive governments repeatedly assert they are keen to assist.

At the risk of appearing cynical – not that, in my experience, being

cynical about the motivations of political parties and governments

carries a serious risk of leading one into making erroneous predictions

about what they might be– I think the answer is obvious. While political

parties and governments profess to care about first home buyers, the

reality is that in a typical year fewer than 100,000 people succeed in

attaining home ownership for the first time; whereas there are some 5.8

million households (and over 8 million people) who already own at least

one property. Hence there are 100,000 votes for policies which might

result in lower house prices, and over 8 million votes against policies

which might result in lower house prices (or in favour of policies which

result in higher house prices). As the Americans say: ‘do the math’.

John Howard – who could ‘do the math’ better than most – often used

to say that no-one ever came up to him complaining about the increase in

the value of their home, or asking him to do things that would reduce

the value of their homes so that younger people could buy them more

readily.

Nonetheless, if by some chance a political party really did want to

advocate and implement policies that really would stand some chance of

improving the capacity of the Australian housing system to respond to

the needs and aspirations of Australian citizens, what might they say?

The fundamental change that such a set of policies might embody would

be a switch from policies which inflate the demand for housing to

policies which boost the supply of housing. Such a suite of policies

might include some or all of the following:

-

first, the abolition of all existing policies which serve only to

increase the prices of existing dwellings, such as cash grants to and

stamp duty exemptions for first time buyers, and ‘negative gearing’ for

investors (in all assets, not just property, and if politically

necessary, only for assets acquired after the date on which such a

policy was announced);

- second, the redirection of the funds thereby saved (and/or the

additional revenue raised) towards programs that increase the supply of

housing – for example, by directly funding the construction of new

dwellings (as the Rudd Government did as part of its response to the

global financial crisis), or by providing some combination of grants,

loans or tax incentives to induce private sector developers to increase

the proportion of ‘affordable’ dwellings within their developments,

whether for sale or rental;

- third, expanding or replicating programs like Western

Australia’s ‘Keystart’ scheme which assist eligible people to become

home owners on a ‘shared equity’ basis, with eligibility being subject

to a means test, and which creates a ‘revolving fund’ as the ‘shared

equity’ is returned to the State Government upon sale;

- fourth, changes to the way in which State and Territory Governments

tax holdings of and transactions in land, with a view to encouraging

more efficient use of it. That would include replacing stamp duty on

land transfers (which are ‘bad’ taxes on many grounds, including that

they discourage people from changing their dwellings as their needs

change) with more broadly-based land taxes (ie, no exemptions for

owner-occupiers, but with appropriate transitional provisions) and

possibly higher rates for undeveloped vacant land in established urban

areas;

- fifth, taking a more ‘holistic’ view of urban infrastructure

investment, by recognizing that it has an important housing dimension –

that is, that public (or private) investment in transport infrastructure

(both public transport and roads) can make a tangible contribution

towards improving housing supply and affordability by making

‘greenfields’ developments more accessible to both buyers and renters –

and considering funding such infrastructure by levies on the increments

to the value of the land which result from such investments (as for

example with the levy that funded the Melbourne Underground Rail Loop

Authority in the 1970s and early 1980s);

-

sixth, revisiting current models for financing the provision of

infrastructure and services in ‘greenfields’ housing estates with a view

to reducing the extent to which these are funded by ‘upfront’ charges

(something which could be assisted by changes to the land tax regime

which I mentioned a moment ago); and

-

seventh, reducing the cost, complexity and regulatory uncertainty

associated with ‘brownfields’ and ‘infill’ developments in established

areas – which doesn’t have to mean traducing the property rights of

other property owners, but which should mean clearer and more uniform

planning rules, with fewer opportunities for frivolous or vexatious

objections and appeals.

Note that I am not advocating something that is often widely assumed

to find favour with economists – namely, the removal of the exemption of

owner-occupied housing from capital gains tax. I don’t favour that,

because consistency with other parts of the tax system would require

that mortgage interest payments be deductible. That would in turn almost

certainly encourage people to take on more debt, and would thus inflate

the demand for housing, putting further upward pressure on prices. And

it could well end up being revenue negative.

Sadly, however, the political calculus to which I referred earlier

means that there is probably less chance of any of these proposals being

taken up – let alone all of them – than there is of Andrew Demetriou

calling a press conference to announce that Tasmania really should have

its own team in the Australian Football League. Politics – more than any

other single factor – means that Australians are likely to have to live

with a dysfunctional housing system for a long time yet to come.